Last week, I walked you through animating the render so that it can convey a sense of movement. But one central part of the entire indicator is to visualize various states of tasks that we might have. To refresh your memory of what the entire purpose of this is, read the first article. To get a quick refresher on what we did last week, click here for last week’s article.

Setting Up the Data Structures

With the animation out of the way, the next construction site to tackle concerns color. Until now, the rays are all just equally colored, and you have probably even changed the color if you were bored. But if you remember, I want to indicate various states in the iris using colors. So let’s add them now.

This is unfortunately very convoluted. I tinkered a lot with the code until I found a proper solution. This solution is what I call “segments.” I define four segments that one can set. Why four? Two reasons. First, shaders are really tight and don’t allow for variable sized arrays. Second, I want to blend the colors into each other, meaning that, if you use all four segments, you will already have eight colors in the circle. Any additional color would drastically reduce the informativeness of the iris, countering its purpose to be quickly comprehensible.

The segments are part of the overall state, so let’s move them there. I use three properties to remember their state (actually, it’s four, but let’s keep it simple for now):

private segmentCounts: Vec4

private segmentColors: Vec4<Vec4>

private segmentRatiosTarget: Vec4

segmentCounts contains the current amount of counts for each segment. If one segment is zero, it will be discarded, so you can use fewer, if you prefer. The idea is that you associate one state with each segment. How I see it: The first segment includes failed tasks. The second segment includes successful tasks. The third segment contains in-progress tasks. (I am still pondering if I should use the fourth for cancelled tasks.) So I provide four colors to the engine in segmentColors: red, green, blue, and (the for my purposes unused segment) purple. I decided to hard-code the colors to ensure they always “pop” and are easily distinguishable from each other. The colors are provided by a simple color map:

this.colormap = {

blue: [0.2, 0.5, 1.0, 1.0],

red: [1.0, 0.3, 0.3, 1.0],

green: [0.3, 1.0, 0.3, 1.0],

yellow: [1.0, 1.0, 0.3, 1.0],

purple: [1.0, 0.3, 1.0, 1.0]

}

As you can see, these colors already follow the RGBA-format used by the OpenGL shaders, for simplicity.

One side note, I defined a new utility type, Vec4 which is simply defined as an array with four numbers. Again, if you use JavaScript, you won’t need that.

I’ll skip the getters and setters for this function, but I need to provide ratios from these counts (because a circle just has 100%, and not an arbitrary count):

const sum = this.segmentCounts.reduce((p, c) => p + c, 0)

this.segmentRatiosTarget = this.segmentCounts.map(c => c / sum)

Next, we have to tell the shaders about this. For this, I decided to use a struct because it makes working with the data simpler:

struct Segment {

float ratio;

vec4 color;

};

uniform Segment u_segments[4];

Each segment has a color (this way, I could modify the colors dynamically if I really wanted to), and a ratio between 0 and 1.

Now we have to tell OpenGL how we can provide the data to the shaders. This requires a few new pointers in the rendering engine:

this.segmentLocs = []

for (let i = 0; i < MAX_SUPPORTED_SEGMENTS; i++) {

this.segmentLocs.push({

ratio: gl.getUniformLocation(this.program, `u_segments[${i}].ratio`),

color: gl.getUniformLocation(this.program, `u_segments[${i}].color`)

})

}

Huh, what is that? One limitation of the shader language is that everything is really tightly guarded, and this includes the memory positions of data. I could have forced the shaders to move the segment colors to very specific memory locations and then address them using indices (e.g., firstLocation + 1, firstLocation + 4 and so on), but that seemed a bit too cryptic to understand in six months from now.

So instead I used a property of WebGL that allows me to get the memory location for each individual ratio and color individually. This is a bit verbose, but remember that OpenGL will retain the last data we have provided, and only update what we explicitly change. So as long as we don’t need new data in those memory locations, we can just not access these locations. This keeps the amount of updating to do during each individual rendering run much lower, as the shaders can reuse existing data.

To set the segments, we can now add a simple function to the rendering engine (and pass this data from our IrisIndicator class):

setSegments (segments: Vec4<Segment>) {

const gl = this.gl

for (let i = 0; i < MAX_SUPPORTED_SEGMENTS; i++) {

const seg = segments[i % segments.length]

let [r, g, b, a] = seg!.color

r *= this.hdrFactor

g *= this.hdrFactor

b *= this.hdrFactor

gl.uniform4fv(this.segmentLocs[i]!.color, [r, g, b, a])

gl.uniform1f(this.segmentLocs[i]!.ratio, seg!.ratio)

}

let blendRatio = Infinity

for (const { ratio } of segments) {

if (ratio === 0.0) {

continue

}

if (ratio < blendRatio) {

blendRatio = ratio

}

}

blendRatio /= 2.0

blendRatio = Math.max(Math.min(blendRatio, 0.1), 0.01)

gl.uniform1f(this.blendRatioUniformLocation, blendRatio)

}

This code requires some elaboration. const seg = segments[i % segments.length] simply ensures that, if someone ever manages to pass in fewer or more segments, this will only use at most four of those, repeating if necessary. The next few lines disassemble a passed in color, and multiply by an hdrFactor. What is that?, you may ask. Well, it is a factor of currently 10 that simply makes the colors “pop” more. This is literally what “HDR” or “High-Dynamic Range” means: Color values that can get much brighter than regular standard definition (SD) colors. I took this advice from the LearnOpenGL tutorials because it will be necessary for the bloom filter, and it works well. This doesn’t really need to be a setting, but if I ever want to revisit this code again, this will come in handy.

(Also, you may want to set this factor to 1.0 until we have implemented tone mapping, which we do in the next article. This way the colors are discernible.)

Lastly, we update each segment location with both its (possibly new) color and its new ratio. Below that follows code that determines the range in which we should blend two adjacent colors instead of returning a solid color. I have found that this blend ratio needs to be dynamically calculated. Since it won’t change for all pixels in a single run, we can pre-calculate this ratio here and provide it for all rendering passes. To use this information, we can now turn to the fragment shader.

Computing Colors

The fragment shader now has access to both the segments and their associated colors and ratios and the blend ratio. It can use only this information to accurately compute a color based on the pixel’s position. To do so, I have after many hours come up with the following monstrosity of a function:

vec4 compute_color () {

vec2 coords = (v_texcoord.xy - 0.5) * 2.0 * vec2(-1, 1);

float rad = atan(coords.y, coords.x) + PI;

float radThreshold = MAX_RADIANS * u_blendRatio;

float segmentStart = 0.0;

float segmentEnd = 0.0;

vec4 prevColor = INACTIVE_COLOR;

for (int i = u_segments.length() - 1; i >= 0; i--) {

if (u_segments[i].ratio > 0.0) {

prevColor = u_segments[i].color;

break;

}

}

for (int i = 0; i < u_segments.length(); i++) {

if (u_segments[i].ratio == 0.0) {

continue;

}

vec4 currentColor = u_segments[i].color;

segmentEnd = segmentStart + u_segments[i].ratio * MAX_RADIANS;

if (rad >= segmentStart && rad <= segmentStart + radThreshold) {

float blendStart = segmentStart - radThreshold;

float blendEnd = segmentStart + radThreshold;

return mix(prevColor, currentColor, (rad - blendStart + 1.0) / (blendEnd - blendStart + 1.0));

} else if (rad > segmentStart + radThreshold && rad <= segmentEnd - radThreshold) {

return currentColor;

} else if (rad > segmentEnd - radThreshold && rad <= segmentEnd) {

vec4 nextColor = INACTIVE_COLOR;

int next = i == u_segments.length() - 1 ? 0 : i + 1;

Segment nextSegment = u_segments[next];

for (int j = 0; j < u_segments.length(); j++) {

if (nextSegment.ratio > 0.0) {

nextColor = nextSegment.color;

break;

}

next++;

if (next >= u_segments.length() - 1) {

next = 0;

}

nextSegment = u_segments[next];

}

float blendStart = segmentEnd - radThreshold;

float blendEnd = segmentEnd + radThreshold;

return mix(currentColor, nextColor, (rad - blendStart) / (blendEnd - blendStart));

}

segmentStart = segmentEnd;

prevColor = u_segments[i].color;

}

return INACTIVE_COLOR;

}

Let’s go through it piece by piece. First, we take the texture coordinates that have been provided by the vertex shader (see my earlier note). Interpolated by OpenGL, this will be one of the pixels that is touched by the vertex shader. We now have to re-transform them back into coordinates that are on the unit circle (i.e., where $x$ and $y$ are between $-1$ and $+1$).

Side note: Why do we have to transform the coordinates into clip space and then back again?! Well, as I mentioned earlier, in between the vertex and the fragment shader, OpenGL will take a look at the output produced by the vertex shader, and determine the affected pixels to provide to the fragment shader. This means that the OpenGL rasterizer needs to take a look at the texture coordinate. In other words, we have to set the texture coordinate to the proper coordinate system, and undo that work in the fragment shader again to get absolute coordinates. This certainly seems superfluous, but there are reasons for doing it this way that will probably make sense for more complex applications.

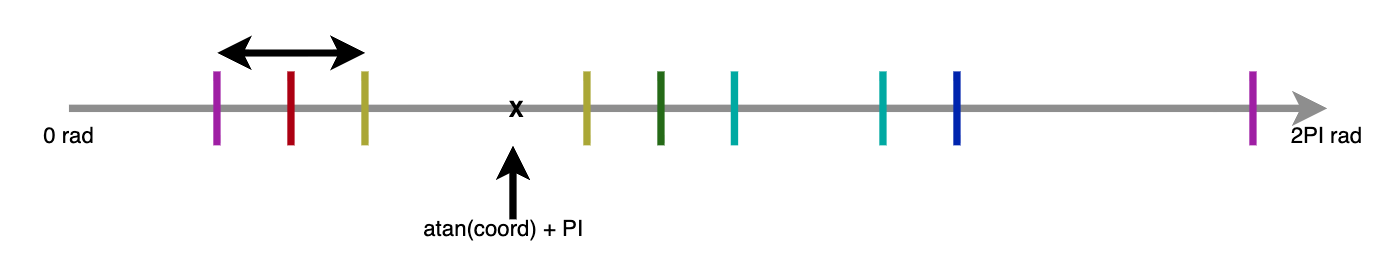

Once we have the coordinates in unit-circle units, we can use a trigonometric function that I myself have never used before to convert the coordinate into the radians that they occupy on the unit circle: the arc tangent. We add PI to it to move the function’s output from the domain $[-\pi; \pi]$ to the associated radians $[0; 2 \pi]$.

Side note: Why wouldn’t a shader that literally deals with numbers not have a constant for Pi?

Lastly, you will see that I multiplied the coordinates with vec2(-1, 1). Like the code I’ve used in the vertex shader to flip the $y$-axis, this effectively flips the $x$-axis. Why do I do that? Well, just as radians have this weird habit of moving counter-clockwise, the arc tangent function has the weird habit of placing its “starting point” oddly. I want the colors to start at the right-center, and move clockwise. The native output of the arc tangent with the addition of $\pi$ would place the start on the wrong side, so by flipping everything along the vertical axis, I fix that.

Now we have information on all the segments as well as where on the circle the current pixel lies, and we can use this to compute its color. I’m not going to dissect the entire function here, but the big picture is as follows: I take the two PI radians of space that we have around the unit circle as a line, where we start with the first segment at 0 radians, and end with the last segment at $2 \pi$ radians.

The rest of the function checks in which segment the pixel actually lies. If the pixel lies in one of the threshold areas (coming from the previous color, or going into the next color), I calculate how far the pixel lies in that threshold area, and mix the two colors based on that. The whole prevColor and nextColor calculations merely ensure that the circle is infinite, meaning the prevColor of the first segment we check is the last segment’s color, and the nextColor of the last segment is the first segment’s color. The code also ensures to skip empty (=unused) segments.

Now we can, very unceremonially, change the fragColor output:

fragColor = compute_color();

That’s it! If you now re-run the code, it should appropriately color each segment, starting from the right-middle position in a clockwise motion. In between the segments, it should blend the adjacent colors for a neat gradient effect.

Animating Segment-Changes

Now it is time to turn to the fourth property I used to store the segment ratios:

private segmentRatiosTarget: Vec4

private segmentRatiosCurrent: Vec4

There are two properties to remember the ratios of the segments. One contains the current ratio, and one contains the target ratio. You hopefully can see where this leads: Whenever the segment counts update, I don’t actually change the current ratios, I only set a new target ratio. The current ratios are only overwritten in the render function, naturally time-dependent. The code is straight-forward:

const step = deltaMs / this.segmentAdjustmentAnimationStepDuration

let hasRatioChanged = false

for (let i = 0; i < MAX_SUPPORTED_SEGMENTS; i++) {

const cur = this.segmentRatiosCurrent[i]!

const tar = this.segmentRatiosTarget[i]!

if (cur === tar) {

continue

}

hasRatioChanged = true

const direction = cur > tar ? -1 : 1

const difference = Math.abs(tar - cur)

if (difference < 10e-4) {

this.segmentRatiosCurrent[i] = tar

} else {

this.segmentRatiosCurrent[i]! += direction * step * difference

}

}

if (hasRatioChanged) {

this.setSegments()

}

This is quite a bit of code, but it works simple. For each segment, we retrieve its current ratio and its target ratio. If both are the same, we are already done. However, if they are not, it will move the current ratio closer towards the target ratio by direction * step * difference. Doing it this way gives us the (accidental) benefit that we have an easing function.

An easing function simply means that initially the changes towards the target ratio will be very fast, and getting incrementally slower as the current ratio approaches the target ratio. Essentially, this is the same as the CSS ease-out function that you might have seen at some point. Finally, to avoid endless loops (since the difference can never reach 0 this way), we “snap” the current ratio to the target ratio if the difference becomes barely perceptible. The number 10e-4 (0.0001) is a purely arbitrary number that I found sufficient.

Finally, this code also ensures that we don’t needlessly update the segment structure if nothing has changed. This keeps performance up as long as you don’t change the ratios. The movement speed is controlled by segmentAdjustmentAnimationStepDuration which you can control on the demo page.

Final Thoughts

At this point, the iris indicator is basically done. And all it took was about 9,000 words (about a regularly-sized research paper)!

The next steps involve doing some post-processing. Specifically, I include three post-processing stages: Multi-sample antialiasing, a bloom filter, and tone mapping.

Everything up until now you could have easily also done in SVG. But it’s the post-processing stages that really set OpenGL apart, and which I was looking forward to the most. So stay tuned for part 6 of this journey!

The Full WebGL Series

Jump directly to an article that piques your interest.