I have this tradition. At least, it appears like a tradition, because it happens with frightening regularity. Every one to two years, as Christmas draws close, I get this urge to do something new. In 2017, I released a tiny tool that has turned into one of the go-to solutions for hundreds of thousands of people to write, Zettlr. In 2019, I wrote my first Rust program. In 2021, I did a large-scale analysis of the coalition agreement of the German “Traffic light” government. During the pandemic, I built a bunch of mechanical keyboards (because of course I did). In 2023, I didn’t really do much, but in 2024, I wrote a local LLM application. So okay, it’s not necessarily every year, but if you search this website, you’ll find many tiny projects that I used to distract myself from especially dire stretches in my PhD education.

Now, is it a good use of my time to spend it on some weird technical topics instead of doing political sociology? I emphatically say yes. If you are a knowledge-worker, you need to keep your muscles moving. Even as a researcher, if you do too much of the same thing, you become less of a knowledge-worker, and more of a secretary. Call it an artistic outlet, that just so happens to make my research job so much easier. The last time I had to think about wrong data structures in my analytical code or when running some linear regression was … let’s say a long time ago. The more I know about software and hardware, the more I can actually focus on my research questions when I turn to the next corpus of text data.

But alright, you didn’t click on this article because you wanted to hear me rationalize my questionable life choices, you want to read up on the next rabbit hole I fell into: OpenGL and WebGL. In the following, I want to walk you through the core aspects of what WebGL is and what you can do with it, what I actually did with it, and what the end result was. If you’re not into technical topics (which, given the history of articles here, I actually have to start to doubt at this point), click here to see the full glory of my recent escapade.

Note: In the following, I will skip over a lot of basics, and merely explain some interesting bits of the source code (which you can find here), central decisions I took, and things I learned. I don’t verbatim copy the entire code that you can find in the repository. The entire thing is still insanely long and will span multiple articles, even though I try to leave out a lot which you can learn via, e.g., WebGLFundamentals, which I recommend you read to learn more.

Background

First, some context. At the end of 2024, someone complained that project exports in my app, Zettlr, were lacking any visual indication of their progress. As a quick primer: Zettlr uses Pandoc to convert Markdown to whichever format you choose. However, especially for long projects, exporting may take quite some time, during which the app looks as if it’s doing nothing. You can still work with the app, and do things, but it’s hard to know when Zettlr is actually done performing the project export. The biggest issue was less finding a way to just tell users which background tasks are currently running, and more how to adequately visualize this to them. For quite a bit of time, my brain kept churning idea after idea in the search for a cool way to visualize “something is happening in the background.” You can read up on many discussions that I’ve had with Artem in the corresponding issue on the issue tracker.

Indeed, the task was quite massive, because the requirements were so odd:

- The indication should convey a sense of “something is happening” without actually knowing the precise progress of the task being performed.

- It should quickly and easily convey how many tasks are currently running in the background, and what their status is.

- It should be so compact that it fits into a toolbar icon.

- It should absolutely avoid giving people the impression that something might be stuck.

At some point, I had my eureka moment: Why not produce an iris-like visualization? Intuitively, it ticked all the boxes: One can animate the picture to convey a sense of movement without looking like a run-of-the-mill loading spinner that we have collectively come to dread; by coloring its segments, one can include several “things” with different status; and by toggling between an “on”- and “off”-state, one could indicate whether something is running, or not.

I currently suspect that my brain simple mangled together the circular appearance of a loading spinner and the logo of 3Blue1Brown into a contraption that would prove to be insanely difficult to create.

Because I wanted to convey a lot of subtle movement, I opted to choose WebGL to implement it, using all the fanciness of graphics processing. My thinking was as follows: I could combine something I’d have to do at some point anyway with something new to learn. I thought: “How hard can it be to learn some shader programming on the side?”

… well, if you’ve read until here, you know that I was rarely so wrong with my estimate of how long it would take as this time. What started as a “let me hack something together in two Christmas afternoons” ended up being an almost two-week intensive endeavor that has had my partner get real mad at me for spending so much time in front of my computer.

But now, it is done, and I have succeeded in achieving exactly what I had imagined weeks ago. To salvage what I can, I am writing these lines to let you partake in my experience, and maybe you find understanding the guts of GPU-accelerated rendering on the web even intriguing!

The Result

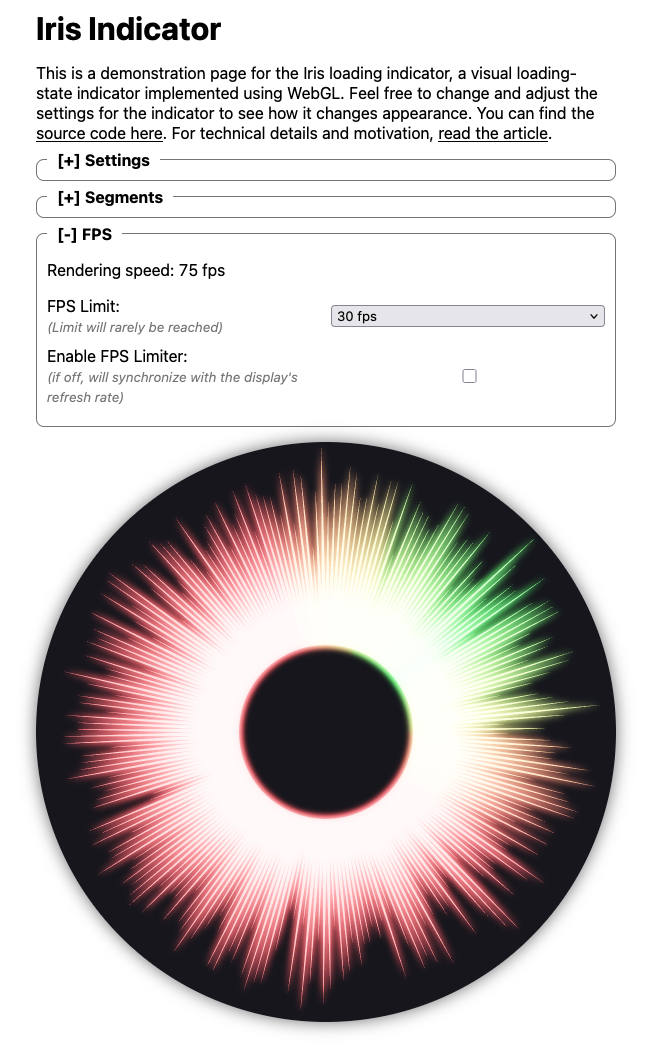

The result of all these efforts is a beautiful iris indicator that subtly moves and changes colors based on the various tasks that are running. I took half an hour to code up a demonstration page so that you can play around with the result.

On the page, there are four sections: Some settings, configuration for the segments, a frame counter, and the actual animation below that.

Let me guide you through the settings first:

- Seconds per rotation: This setting sets how long it takes for the indicator to rotate once around. By default it is set to 120 seconds, so two minutes, but you can turn it down to increase its speed. The minimum setting is 10 seconds which is quite fast.

- Ray movement speed: This setting determines how fast the individual rays will increase and shrink in size. It is pre-set to five seconds for one full movement, but you can turn it down to increase their speed. The minimum is 100ms, which is stupidly fast.

- Enable MSAA: This enables or disabled multi-sample antialiasing. If disabled, the animation can look very rugged and pixelated.

- Enable Bloom Effect: This setting enables or disables the bloom effect which makes the entire indicator “glow.” This can actually reduce the performance of the animation quite a bit, but it also has a great visual impact.

- Bloom intensity: This effectively allows you to determine how much blurring will be applied to the image. It is preset to 2×, which is a good default. You can reduce it to 1× which will make the effect more subtle. A setting of 8× may be a bit much, but I decided to leave it in since I feel it is instructive.

- Rendering resolution: This setting determines how detailed the resolution is. It is preset with whatever device pixel ratio your display has. If you’re opening the website on a modern phone or on a MacBook, it will probably be preset to 2×, but on other displays, it will be 1×. It has a moderate performance impact.

- Segment adjustment step duration: This setting determines how fast the segment colors adjust when you change the segment counts in the next section.

The next section allows you to determine the segments that will be displayed. As a reminder: The whole intention of this project was to visualize the status of running tasks, which might be successful, unsuccessful, or still en route. You have four segments available, and can determine how many tasks are in each segment, alongside their color. The colors are hard-coded because this way I can ensure that they all fit and blend together well.

By default, the demonstration page will auto-simulate changes to the segments so that you don’t have to click around. When the simulation is active it will, each second, determine what to do. There is a 30% chance each that one of the first three segments will be incremented by one. Further, there is a 10% chance that the simulation will reset everything to zero and start again.

The last section includes settings for the frame rate. The frame rate simply means how often the entire animation will be re-drawn (hence, frames-per-second). At the top, it displays the current frame rate. The frame rate is bound to your display, so on a MacBook (which has a refresh rate of 120 Hz), the frame rate will be at most 120 frames per second. On my secondary display, the frame rate is 75 Hz.

By default, I have implemented a frame limit of at most 30 frames per second. This ensures that the animation is still smooth without being too demanding on your computer or phone. However, you can change the frame rate to, e.g., 60 fps. This will render the animation twice as frequently. Especially if you turn the rotation speed to the max, you actually want to increase the frame limit, because on 30 frames per second, it can indeed look very stuttery.

Feel free to play around with the settings to see how they change the animation. Again, you can also go through the source code of the animation to learn how it works.

About This Article Series

Over the next three months, I will publish one part per week on how I finally managed to achieve this feat. The logic behind it is very complex, and it takes a lot of research to understand how to achieve the various effects. The articles will be as follows:

Setup

In the next article, I will introduce you to WebGL, OpenGL, and how to set everything up to actually start doing things with WebGL. I will talk about the basic architectural decisions I took, and how code can be properly organized. I will also introduce you to OpenGL’s rendering pipeline, and how it works.

Drawing Things

In article three, I will guide you to drawing the rays that make up the iris. You will learn about how to provide data to OpenGL, and how the drawing actually works.

Animation

In the fourth installment, I will talk through how to add two of the three animations that make up the iris: rotation, and the movement of the rays. This article almost exclusively focuses on JavaScript, and contains minimal changes to the shaders, because movement is mostly a thing of JavaScript.

Computing Colors

In article five, I will introduce you to the algorithm I designed to both color the segments of the iris according to the number of running tasks, i.e., the main goal of the entire endeavor. I will also explain the final, third animation that the indicator includes: animating the colors of the iris.

Enabling Post-Processing

This article will be more in-depth and explain another big part of OpenGL’s rendering pipeline. It explains how to enable a renderer to perform post-processing. It also adds one post-processing step: tone-mapping.

Adding a Bloom-Filter

Article seven focuses on the centerpiece of the animation, the one big part that would not have been possible using other techniques such as SVG. I explain how to add a bloom post-processing step in between the ray rendering and the output, and how bloom actually works. (It’s surprisingly simple!)

Adding Multi-Sample Antialiasing

In the eight and final practical article in this series, I explain MSAA a bit more in detail, why it sometimes works, and sometimes doesn’t, and how to actually add it to the animation. I also explain the final piece of the OpenGL Rendering pipeline that you probably need to know to understand what is happening.

Concluding Thoughts

When I set out to create this animation, I imagined it would take me maybe two days — nothing to write home about (literally). However, I was wrong, and, to the contrary, we are now looking towards an astonishing nine (!) articles just to explain what has happened here.

I found the journey extremely rewarding, even though it ate up my winter holidays. I want to let you partake in what I learned, and I hope you stick along for the ride.

So, please, come back next Friday for part two: Setting everything up!